Restoring Control on a High-Attention Bottling Line

How reclaiming engineering focus mattered more than reducing downtime

When our customer reviewed performance at their facility, one line had become a persistent concern.

Filling 20oz and 1-liter bottles, Line 1 was increasingly difficult to run predictably. Downtime events were frequent and sometimes extended. Even when the line was running, it required constant attention to keep it stable. Operators and maintenance teams spent more time reacting to issues than improving performance.

This was not the result of neglect. Line 1 reflected years of reasonable decisions made to keep production moving - equipment changes, partial upgrades, and workarounds layered onto an aging control foundation. Like many long-running production systems, it carried the accumulated complexity of its own history.

“What really pushed this line to the top (of the priority list) wasn’t just downtime. It was how much controls engineering attention it consumed.”

— Engineering leader, beverage manufacturing

What ultimately elevated Line 1 from a “problem line” to a priority was the resource burden it placed on the organization. Troubleshooting Line 1 repeatedly pulled experienced controls engineers away from other lines, longer-term improvements, and coaching newer team members. The risk was no longer confined to one asset - it was constraining the broader engineering system.

A control system at its limits

At the core of Line 1 were legacy PLC platforms supported by DeviceNet and DH+ networks. These technologies had served the line well for many years, but were becoming increasingly sensitive to power disturbances, component failures, and network irregularities.

Several factors combined to increase risk:

Repeated drive failures tied to power quality issues

DeviceNet faults that could cascade and stop large portions of the line

A DH+ network whose physical topology no longer matched its original design

Documentation that lagged behind years of incremental changes

When an experienced programmer left the facility, the remaining margin for error narrowed further. Newer engineers had limited exposure to legacy networks, making even familiar issues harder to diagnose and recover from.

The system could still be made to run - but it was increasingly difficult to recover when something went wrong.

“DeviceNet works - until it doesn’t.

And when newer engineers haven’t grown up with it, even knowing where to start becomes a problem.”

- Controls engineer

Incremental fixes helped in the short term, but they did not change the underlying fragility. Line 1 needed more than stabilization. It needed its control foundation restored.

From stabilization to deliberate restoration

IKONIKA was initially engaged to help address failures. As work progressed, both teams developed a clearer picture of the system as a whole.

The conclusion was not that everything needed to be replaced, but that the control architecture itself needed to be restored deliberately, with minimal disruption to production.

Several constraints shaped the approach:

Production risk had to be minimized

Existing field devices and I/O needed to be preserved

Certain legacy equipment could not yet be replaced

The shutdown window was fixed and could not be exceeded

The technical scope included:

Consolidating multiple older PLCs into a single modern control platform

Migrating line-level communication from DeviceNet to Ethernet

Retaining DH+ only where required to communicate with the filler

Replacing obsolete drives and network hardware

Converting panel power distribution to 24V DC

Reworking panel internals while retaining existing enclosures and field wiring

Upgrading panels in place required more engineering effort, but it reduced restart risk by avoiding unnecessary disturbance to thousands of existing terminations.

Nine days, no overruns

A carefully negotiated nine-day shutdown window defined the project. Production had to restart on time. Overrunning the window was not an option.

Execution began immediately after Thanksgiving, with work starting the Saturday following the holiday. The early days of the shutdown were intentionally resource-heavy, with multiple workstreams progressing in parallel across panels, networks, drives, and controls.

The scope of work required coordination across a large installed base. More than sixty variable frequency drives were replaced, tested, and commissioned during the shutdown, alongside network and control system changes. The volume of work reinforced the need for disciplined sequencing and clear standards, particularly during restart.

Progress was deliberate rather than rushed. The goal was steady movement toward a clean restart, not last-minute acceleration.

Making the hidden visible

On Line 1, the challenge was not that information had slowly disappeared. It was that the system had never been designed to be modified through the interface. Changes were routinely made directly in code rather than through parameters exposed on the HMI. Over time, this meant that critical operating behavior existed in logic rather than in places operators and maintenance teams could see or adjust intentionally.

As a result, understanding system state required experience, memory, and access to the program. Troubleshooting depended on knowing where to look in the code rather than being able to observe how the system was behaving. As staffing changed, recovery became slower and more dependent on a shrinking group of people with historical knowledge.

A central goal of the upgrade was to reverse that pattern.

The system was made simpler, more modifiable, and more observable.

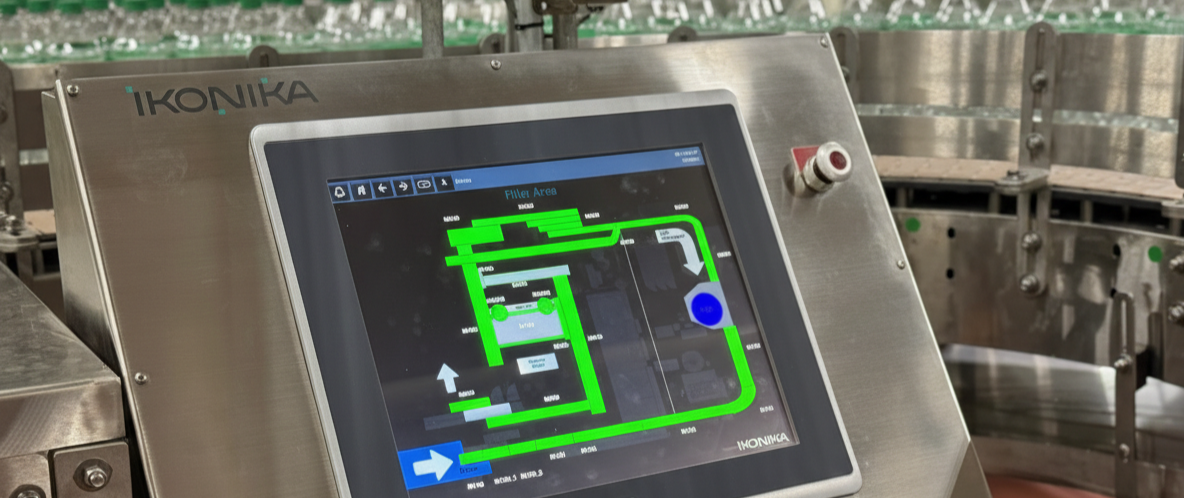

Network architecture was simplified through the move to Ethernet, reducing complexity and making it easier to add, remove, or diagnose devices. At the same time, operating parameters that had previously been buried in code were intentionally surfaced on the HMI, allowing operational changes to be easily made in a controlled manner.

Key operational information was surfaced directly on the HMI: network health, device status, input conditions, and protection states that previously lived only in panels or devices. This expedited troubleshooting. Instead of inferring state from symptoms, operators and maintenance teams could see the system as it was behaving in real time.

This visibility also changed how adjustments were made. Conveyor speeds were no longer tuned by trial and error or hidden parameters. Relationships between conveyors were shown explicitly, allowing discrepancies to be identified and corrected intentionally. Controls that once required specialist intervention became understandable for the operators.

By moving behavior out of code and onto the screen, engineering effort shifted from fault finding to resolution.

“It wasn’t that the network never worked. It was that nobody could explain how it worked - or how to fix it if it failed.”

- Engineering leader, beverage manufacturing

Rather than working around these uncertainties, the joint customer and IKONIKA team traced the DH+ network, cable by cable. Dead ends were identified. Termination was corrected. The effective topology was brought back into alignment with how the system was intended to behave. This work was slow and exacting, but it replaced ambiguity with clarity.

The outcome was a legacy DH+ network that could coexist predictably alongside a modern Ethernet backbone. When issues arose, they could be reasoned about directly rather than inferred from symptoms or tribal knowledge.

In brownfield systems, legacy networks do not need to be replaced to be acceptable. In this case, the DH+ network needed to be clearly documented so future maintenance would not depend on guesswork.

Restarting production: vertical startup

Despite the scope of work, the restart proceeded smoothly.

Commissioning followed a defined sequence. Communications were verified. Drives and motion were tested. Speed setpoints were validated. The line was run in automatic mode before production resumed.

Success was measured by vertical startup returning to stable, productive operation as quickly as possible. Line 1 met and exceeded its planned startup curve, with no controls-related delays. Issues encountered during startup were mechanical in nature and unrelated to the control upgrade.

“I would say it’s about as vertical startup as I’ve seen in the last year. We planned on 50% production the first couple days and we greatly exceeded that curve.”

- Engineering leader, beverage manufacturing

Production returned on schedule, without the prolonged instability that often follows major control changes.

What changed for the people running the line

After the upgrade, Line 1 became significantly easier to operate and support.

Operators moved from text-based motor lists to a visual representation of the full line. Conveyor speeds were shown as a waterfall, making relationships and discrepancies immediately visible. Speed adjustments could be made intentionally - relative to upstream conveyors or benchmarked to the filler - rather than by trial and error.

Maintenance teams gained access to meaningful diagnostics: network health, input status, and configuration visibility that previously required code access or guesswork.

“We didn’t just make the system more reliable. We gave operators and maintenance the tools to understand it.”

- Josef Boyar, IKONIKA

Problems still occur as they do on any production line, but diagnosis is faster, and responses are more deliberate.

Execution under pressure: the human system

The technical outcome was inseparable from how the work was executed.

The shutdown required long days, parallel effort, and coordination across multiple disciplines. The team included a mix of experience levels, with senior engineers setting standards and coaching happening in real time at the panel, on the floor, and during commissioning.

Learning happened during execution, not afterward.

“We define ‘done’ very clearly.

Done means stable, understandable, and supportable - not just running.”

- Josef Boyar, IKONIKA

Calm leadership mattered. Decisions were made deliberately. Problems were addressed directly, without urgency turning into pressure.

“When people know they’re supported, they’re willing to take on hard work. That’s how a mixed-experience team pulls off something like this.”

- Neel Dalwadi, IKONIKA

A familiar hesitation - and a familiar outcome

Many manufacturers recognize the hesitation that precedes projects like this. Modernizing a running production line carries risk. Incremental fixes often feel safer in the moment.

What Line 1 demonstrated is that delay has its own cost - not just in downtime, but in how much skilled attention a fragile system continues to consume.

“You either live with the risk that you currently have in your systems - which most people understand is causing significant downtime - or you take action and go solve the problem. I was very confident in their ability to do that, because they understood the problem and the need.”

- Engineering leader, beverage manufacturing

By planning carefully, executing within a fixed shutdown window, and restoring control without unnecessary disruption, our customer transformed its most high-attention line into a stable, governable system with a clear future.

“This wasn’t about new technology for its own sake. It was about restoring control - technically and operationally.”

- Jon Edwards, IKONIKA